Isabel Sadurni for ACE: Can you talk a little bit about how and why you started this project?

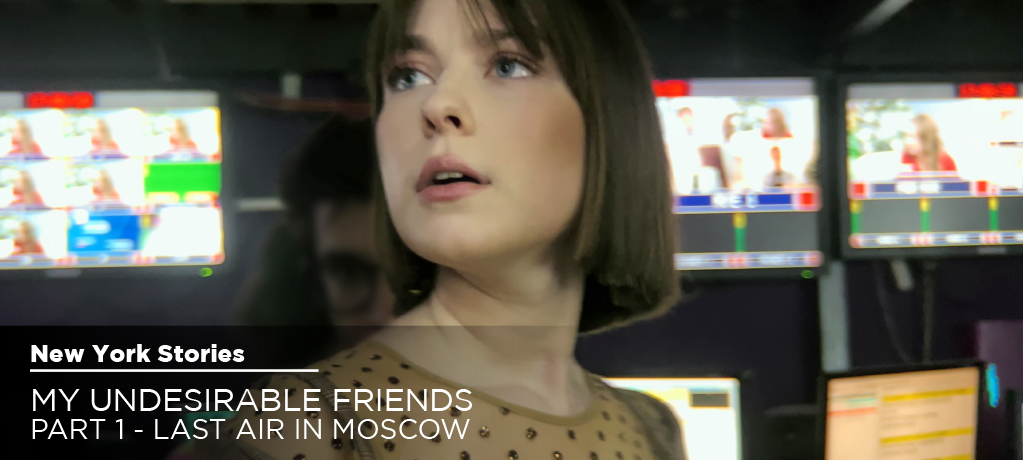

Julia Loktev: I started shooting in October of 2021, four and a half months before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. I started out shooting a different movie than what it ultimately became. In late summer of 2021, I read a story in the New York Times about Russian independent journalists who had just started being declared “foreign agents” by the Putin regime who were fighting back with dark humor. It had a photo of these two cool-looking girls that looked like someone I might meet on my street in Brooklyn, except the Russian government had deemed them “foreign agents.”

I’m originally from the Soviet Union, and I was nine when I came to the US, so I followed news from Russia and I had friends there that I’d made as an adult, including Anna Nemzer, a journalist at TV Rain who is also co-director of the film. TV Rain was Russia’s only remaining independent television channel. It’s where people, for example, watched Navalny’s return to Russia live. If you’ve seen the documentary Navalny, a lot of the footage in that film was from TV Rain.

Anna and I thought the film was going to be about a society declaring journalists and activists “foreign agents,” in effect, forcing people – to mark themselves as “other.” I remember thinking what if you could have filmed in Germany in 1935, when the Nuremberg laws were first passed and people were first forced to mark themselves as “other.” I had no idea I would be capturing a society on the eve of starting a full-scale war and turning to full-blown fascism, and that I would be capturing the last days of the opposition fighting from inside Russia before all independent media was shut down in Russia and a million people fled into exile.

Russia had, of course, started a war in Ukraine in 2014, but it seemed to be a level of war that, absurdly and wrongly, the world had gotten used to enough to let Russia host the World Cup. No one expected the kind of full-scale war that Russia would start in February of 2022.

IS: Given that so much of the story changed from your original conception of it, how did you approach the material structurally?

JL: I thought I was filming a feature film, and then history started unfolding in front of me and I had to keep shooting. We got the chance to live through history in real time with our characters. And it turned into a documentary epic in multiple chapters. Part I – Last Air in Moscow all takes place in Moscow in the months leading up to the full-scale war and the first week of the war is 5 ½ hours. We are now working on Part II – Exile.

After I had whittled the footage down from about 300 hours to about 80 hours, I showed it to Michael. He was the first person to see the footage.

Michael Taylor, ACE: We had this amazing first week where Julia and I watched the footage for 5 days straight, for 8 or 9 or 10 hours each day. I had never done a documentary series or a 5-and-a-half-hour film. But the material called out for a more expansive approach. There was so much detail and depth in the lives of these characters as they struggled day by day. Julia was constantly present with her iPhone, right in people’s faces, so the footage is very intimate. Consequently, we were able to cut the film so that it felt like these characters are talking directly to the viewer. The frame was a window on this sort of oppositional journalism and activism as it existed in late 2021.

JL: Which is impossible to imagine in Russia today. I was shooting with an iPhone X then I upgraded to the 13 and 14, which responded to dark situations much better, and I had a little external 58 mm lens. That camera physically required me to be so close to the character, so it wasn’t fly-on-the-wall observational. It was more fly-in-your-lap. You’re really living life with the characters, hanging out in kitchens, taxis, at work.

Michael and I have worked together on two fiction features before this [Day Night Day Night, The Loneliest Planet], and as soon as he started editing, he said, “I’m just going to approach these scenes as if they’re actors, to think where do I feel them.”

MT: Julia had known journalist and TV host Anna Nemzer (Anya) before starting the film. But most of these characters she met for the first time on a Zoom meeting before she came to Russia. You look at the footage, and you get the feeling that Julia has known these people forever. There’s an incredible openness. I think that comes again from the camera and being patient, so they become completely comfortable with Julia and her iPhone inches from their faces.

JL: I’m very grateful to them for how open they were.

IS: I imagine there’s a kind of immediate solidarity as fellow media makers under the circumstances.

MT: Something that taps into that is Anya’s dinner party near the start of Chapter 1. It was the first footage I watched, because that’s literally the first thing that Julia filmed. She had landed that day.

It’s a typical Anya-type dinner party with 10 or 12 activists chatting about the fact that [Dimitry] Muratov got the Nobel prize that day, not Navalny, so you get an overview of where Russian politics and journalism are at that moment. This was about 6 months after Navalny returned to Russia and was immediately jailed. Originally, that’s how the film opened. Then we decided the viewer needed a primer on Anya and TV Rain upfront, so we shuffled the order.

The beauty of the footage was simply bearing witness. Julia does not guide her characters. It’s simply happening. It’s like watching a cat. The cat’s going to do what the cat is going to do. And these journalists, they’re going to do their laundry, they’re going to show you some T-shirts they’ve designed.

One of my favorite scenes is when Ksyusha goes to the post office by the prison where her fiancé is imprisoned. She hasn’t had any access to him for more than a year, and she’s creating care packages for him. You see box after box of Oreos, Cheetos, and instant coffee being lovingly packed. If we were making our own Dardenne Brothers-style movie, I don’t think we could have composed a better scene. But it was real life, and truly emotional.

We wouldn’t look at a scene and say, “Well, this is the one where we learn that the government has come down on this aspect of society.” Instead, we asked, “What struggle is this character engaging in at this point? What is important to them?”

In my own work, I do go back and forth between documentaries and fiction. And a few years ago working on Semi Chellas’ American Woman, I had this revelation which I wrote about in an article for Filmmaker Magazine, which I called “The Art of Listening.” I realized that actors will tell us what the scene is really about. Ignore the script. Watch what the actors do. See what you respond to. And that’s exactly what we did here.

JL: I shut up most of the time very deliberately during the shooting. I didn’t want to center myself. I heard a talk by Bob Woodward once, and it was one of the best lessons ever. He said, “You just have to shut up.”

MT: You have to remember, that this entire film is handheld by Julia, and the camerawork is steady and patient. Every editor wants the shot to go on as long as possible. An editor never wants a cut to be forced upon us. That’s one reason why I found the footage so remarkable. Julia let these people guide her. She didn’t guide them. She didn’t shut them up.

JL: I don’t shoot B-roll. For example, when we see Moscow, we really see it only in the window of the car behind our characters. I’m really focused on the characters, and I can be very patient. And then it’s a matter of distilling the essence of the scene in the edit.

MT: I knew working with Julia that we weren’t going to have cutaways to work with. We weren’t going to have traditional reaction shots. It’s just a matter of “you find a way,” and Julia is especially good at finding ways to connect things that might not normally connect in editing.

When we did The Loneliest Planet, we ended up with about 106 shots in the entire film, because after the beginning they’re all 3- or 4-minute long single takes, very beautifully staged one-ers, with no visual cuts whatsoever. A huge amount of sound editing went into all of those scenes – that’s how we were able to shape them. Everything I’ve ever done with sound in film I’ve learned from Julia.

There’s another thing. This film has a very different pace from The Loneliest Planet. It’s closer to Day Night Day Night, in the Times Square section. We’re very much going moment to moment to moment to moment in the film and there’s a lot of time compression in terms of keeping the pace going.

As far as our editing process for My Undesirable Friends: Part I, we passed everything back and forth. Julia would give me a bin, and she would call it “Master and Selects: 1st scene.” And she might give me 30 minutes, and say, “See if you can turn this 30 minutes into 15 minutes. Call it an assembly. Please don’t make it too polished. I just want to see how you see the material.” Am I describing that correctly?

JL: We really worked in scenes, and it’s a process of distilling each scene, finding the core of a scene. I shoot a lot because I don’t know what’s going to happen and I’m not trying to control what’s going to happen. So there’s a lot of nothing in between. Let’s say there was 4 hours of raw footage for a scene, and I would do a pass to throw out the garbage and cut that down to maybe 1 hour and have that subtitled. Then cut it down to maybe 40 minutes of selects. Then I’d pass it to Michael who would cut it down to, say, 20 minutes. It was really important to me to see what he responded to, what he found interesting. Then, he’d give it back to me and I’d cut it into a 5 minute scene, because I love editing and I love fine cutting. I’m very specific about what frame I cut on. I can micro tweak forever. I often cut on sounds, on a sharp sound. I like when you feel the cut. I want the cut to be a little disturbing, a little surprising. Where I think Michael is so incredible is thinking about the big picture. So once we had cuts of all the scenes, then we’d sit down and watch an assembly of the entire chapter together, and start to think of the big picture of the chapter and adjust the scenes from there. And Michael is an incredible judge of performance. For my fiction films, I operated and Michael sat behind me in the proverbial “director’s chair” and would say, “That’s good. That’s not good. She’s really great in this scene.” He was basically doing my job. And I was doing the reverse. It’s so important having that collaborator who knows the footage inside out, who can write it with you. It’s not so much hands you need, but a brain.

IS: And a heart. Someone who’s really feeling the film.

JL: Exactly, and Michael is very instinctual. He will tell you when this moment doesn’t feel true, whereas I might be focused on the precise rhythm of something. In that way, we’re a very good team.

And he never stops thinking. The next day, he might say, “It was bothering me last night when I thought about this moment that doesn’t quite ring true. What if we connect this to this?” And usually I say, “No, no, no, no, it has to be this way.” And then, a day later, I’ll say ,“You were so right. I should have listened. You’re right.”

MT: On our previous films, I had learned with Julia that if I made an argument for something and Julia said, “No, no, no,” to just let that go for a little bit, and maybe it would come back. Maybe it wouldn’t.

With this film, I started to realize that certain characters fulfilled different roles within the scenes.

JL: We very much thought in terms of editing it like you would a fictional workplace series where in each episode one character comes to the foreground.

MT: Right. So for instance, I felt Sonya is one of our most accessible characters. The way she shared her own experience through showing us her house, saying things like, “We thought maybe I’ll decorate this living room, but we don’t know how long we’re going to be here,” and then, a month later, “Now, we have a sofa!”

JL: Something that so much of the film is about is how everyday details convey a bigger picture. For example, there’s a scene where one of the characters shows us a couch she just bought. She had been declared a foreign agent by the Russian government a few months after she moved into an apartment with her boyfriend. So when we first meet her, she has this almost completely empty living room because she doesn’t know how long she is going to be able to stay in the country and keep working as a journalist. And when we come back in Chapter 2, she announces, “We bought a couch!” It means she is planning to stay; she thinks she still has a future in Russia. Of course, this scene was shot in December, and two months later she has to flee because Russia shuts down all independent media and starts jailing people for just calling the war a “war.”

MT: All of these characters are now living in exile. We’re currently editing the next section of the film, Part II – Exile, where we continue following these characters as they move from country to country continuing their work outside Russia. There are hints of the storm that’s coming as we move from chapter to chapter. For instance, you meet this young guy, Daniil, briefly in the first chapter, who has been declared a “foreign agent” and is talking about moving to Poland. Then, one chapter later, we see Sonya say, “Here’s the plant that he left me.” So we know he is not there anymore. He’s in Poland. But she has the plant. She’s showing us a plant, but it means more than that.

IS: I wanted to ask about something that I really appreciated about the film which was this ability to weave humor and levity throughout a very dark narrative. How intentional were you about that? There were obviously moments I’m assuming that came organically, and you welcomed and incorporated those. Were you also rhythmically aware that the audience needs a break and “Let’s watch the cat” for a moment? Can you talk about finding the emotional balance of the film?

JL: I think there’s humor in The Loneliest Planet and Day Night Day Night. There’s dark humor in my first film Moment of Impact which is about my dad being hit by a car. It’s how my mom and I dealt with that event, a trauma which most people think would not invite humor. But of course, there are inappropriately funny moments in the most tragic events in life. It’s always been how I’ve dealt with the most difficult situations in my life. It’s just in my DNA.

I’m instinctively attracted to those moments. This is aside from the fact that our characters are naturally very funny. For example, Ira and Alesya, two of our journalists – their office has been searched, they know it’s bugged, there’s a drummed-up criminal case against their editor and he’s had to flee the country, they continue to work in their office, and they live constantly in fear of being followed, of someone showing up at their door. And they tell this story about how Ira’s doorbell rings one night and she thinks she’s about to be searched. So she puts on “search appropriate underwear.” They then discuss what is “search appropriate underwear” that it has to be not too embarrassing, but it also has to be comfortable enough, because you might be in jail for several days. To me, that’s what brings it home because that’s what I would be thinking of if I thought the police were at my door, and I might be hauled to jail, and I was in my nightie. I would also be thinking, “What kind of underwear am I going to put on for the next few days of sitting in jail?” That’s a very normal human reaction and it is funny, but it’s also very real. To me, it’s how we process the most difficult events.

MT: One thing that was also important to us is that we wanted to show the work process of these journalists. Some of them make work you can show in videos, like TV Rain, or Important Stories, which is Ira and Alesya. This work is on websites or YouTube. Some work in print for publications like Novaya Gazeta – that’s Lena. We knew we needed to show them actually doing the work of a journalist and what does the work look like? In the case of Anya, because she’s one of the prominent journalists at TV Rain, we could use TV Rain footage to show us “this is what’s happening.” Lena is a phenomenal writer. She has a book out called I Love Russia, which I recommend everyone to read. For Lena’s work scenes, we came up with this device of seeing her typing and then seeing her words appear on the screen.

JL: We knew that we needed to see their actual work, what they’re writing about to explain why the Putin regime would not be happy with these journalists.

IS: Being in the company of people marked as “foreign agents,” did you ever feel that you were in danger? Or concerned that your iPhone would be confiscated?

JL: In terms of danger, I was constantly aware of it when I was around my characters, and I stayed in Moscow during the first week of the full-scale war when the US Embassy was telling Americans to leave while there were still flights. Flights were being canceled almost everywhere and I stayed. At that point, Brittney Griner had been arrested, but this was about a year before Evan Gershkovich was arrested. So I thought, I’m not a famous basketball player. Nobody’s really interested in me. I told myself that “I’m going to stay as long as they’re here,” and I stayed until all my characters fled the country that week and I had nobody left to film there … As they continued to report the truth of the war, they were getting constant threats. I did recognize someone could come into the TV Rain studio any moment, and god knows what, arrest us all, shoot us all up? I was aware of the dangers they live with constantly in their work, dangers they continue to live with in exile. There was actually an Opinion piece in the New York Times just this last week [September, 2024] called “Putin Is Doing Something Almost Nobody Is Noticing” about the Russian Secret Service pursuing activists and journalists abroad that mentioned physical threats to two of our characters. Whatever risks I took feel negligible compared to the risks they take continuing to report the truth. And certainly in comparison to the risks of just a regular person living in Ukraine now.

MT: As we were ready to start sharing the film, we started having these screening club sessions where we invited about 15-20 people to Julia’s apartment and projected each chapter. We’d have one chapter and then a month later we’d have another. We realized we could only invite the same people each month. We couldn’t shift it around because you needed to have seen Chapter 1 to understand Chapter 2. So we developed this core group of people who stuck with us pretty much through the whole edit.

JL: And they were the ones who really encouraged us to get Part I out now as we work on editing Part II – Exile.

MT: I really do think that the individual parts are wonderful, but when you take the cumulative effect of watching all of them together, it adds up to something even greater.

Find additional coverage of the film here:

The Best Doc of the Year Is Like a 5.5 Hour-Long Panic Attack, Vulture.com, October 5, 2024,

At the New York Film Festival, the Most Innovative Work Is Non-fiction, New York Times, October 6, 2024

My Undesirable Friends: Part 1 — Last Air in Moscow’ Review: A Scary and Riveting Portrait of Russia’s Last Independent News Channel, indiewire.com, October 2, 2024