In Honor of the 40th Anniversary of the Right Stuff

ACE Member News, ACE News (Home), ACE Presents, Movies

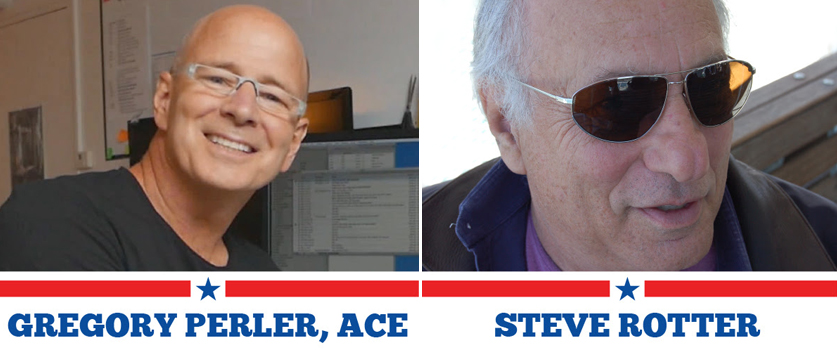

Gregory Perler, ACE, Interviews Steve Rotter

October 2023 marks the 40th Anniversary of the premiere of The Right Stuff, a film based on the best-selling book by Tom Wolfe, written for the screen and directed by Philip Kaufman, and produced by Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler for the Ladd Co. and Warner Bros.

It chronicles the story of U.S. test pilot Chuck Yeager breaking the sound barrier and the beginning of the space race between Russia and the U.S., resulting in NASA’s Mercury program and the selection of America’s first astronauts … men who had the right stuff.

While the film was not a financial success, it was nominated for eight Academy Awards including Best Picture and it won four, including Best Editing. The recipients of that award were Tom Rolf, ACE, Lisa Fruchtman, Douglas Stewart, Glenn Farr and the subject of this interview, Stephen A. Rotter.

I saw The Right Stuff when it released and have loved it ever since. I also have a personal history with Steve – we were co-editors on Enchanted (2007). Over the course of the year that we worked together I remember badgering him for stories about the making of it. As affable and gregarious as Steve is, I got almost nothing out of him. Until now.

And so this is not exactly the story of the editing of The Right Stuff, it’s the story of Steve Rotter and how he came to join Philip Kaufman and his illustrious team of editors to make a classic film.

Steve Rotter: I had to go back to look at the credits of The Right Stuff because I forgot last names…

Gregory Perler, ACE: How did you come onto it?

SR: After I did The World According to Garp, which was my first feature film, I got a call to come out and help Carroll Ballard on Never Cry Wolf. He had mostly cut the movie by himself and so I was only going to be temporary. The producer screened the movie with me and then I met Carroll and he would only let me work on certain things. I worked for two or three weeks everyday until 2 a.m. and he didn’t say very much … he had me work on all the dialogue scenes except one because he said, “I’m happy with it.” So then I look at the scene he doesn’t want me to cut and there’s a flub right in the middle of it.

And so finally when I left I said, “Carroll there’s this scene with a flub right in the middle, you don’t have to do that … you can adjust it and cut around it.“ But when I went to a screening of the final film the flub is still there in the audio!

So then he recommends me to Phil (Kaufman) and Phil hired me sight unseen.

In some ways it was like a factory. It was in a warehouse in San Francisco, and they built a theater right in the warehouse with cutting rooms around the theater.

You would cut a scene and Phil would have you march in and show it to everybody and initially when I came on I was flabbergasted because I would show a scene and there would be all this criticism … some people were very competitive, and I would just pooh-pooh it because I was probably more competitive than anybody at that stage. So I ended up doing whatever I wanted. I was very argumentative, but Phil would back me up.

GP: Like the astronauts were competitive … they’re all working together but competitive.

SR: Yeah, exactly. And the only person I kept in touch with after the film was over was Tom Rolf. Lisa Fruchtman I don’t think I saw; then there was Doug Stewart who was older and had been Phil’s editor on other projects. He had a young wife and young kids and he would go home to them in L.A. on weekends and I swore he came back to work to rest! A sweet guy and very confident. And then Glenn Farr was like the manager of everything … in addition to editing he was also in charge of schedules and all the stuff that I hate.

I remember that when I got there they screened the movie and I think it was five-and-a-half hours long and we had to take a break in the middle. I can’t remember what my thoughts were after that first screening but I did have the feeling that they were in trouble. It just needs time and work. I still think the movie is too long even now, it’s over three as I remember.

GP: Were you brought on because they were behind and needed more manpower?

SR: They started off with Doug, Lisa and Glenn. There was well over a million feet of film and don’t forget all the stock footage – in 8mm, 16mm and 35mm … all of that took place early on and Walter Murch, ACE, was one of the editors. When he bowed out to direct Return to Oz I imagine it must’ve been traumatic for Phil because Walter was the guru of San Francisco and also an extremely gifted guy. Walter was and is extremely intellectual about anything to do with film. He always has a theory about something, which is valid but, you know, to me I don’t want to talk about it I just want do it. I’m asked questions why I did this, why I did that and I can’t really answer them. I mean I can for some movies: I did that because the actor forgot his lines and had to cut around him. I mean, even the movie we did (Enchanted), where she’s coming from one world to another or like the scene in Central Park, it was just, like, the only way you could do it.

GP: Yes, but I seem to remember in those cases we didn’t have a lot of coverage.

SR: Right. And my guess is, and I don’t know because I haven’t spoken to him about it, but my guess is while Walter’s editing he’s more instinctive than you’d think. But I must say he’s the renaissance man of film and became a folk hero in San Francisco. So it had to be a blow when he left, although Phil never referred to it but still, you lose your guy who’s considered to be a genius, it’s got to hurt. Later on he returned to cut Unbearable Lightness of Being for Phil.

GP: It’s amazing how smooth the film is. It doesn’t feel like a patchwork.

SR: Well that you have to give to Phil – he was the architect and he got it the way he wanted it. What Phil did brilliantly was take stock footage and stage scenes around it and in it. It was amazing how he kept all that in his head.

I thought that in terms of direction that film was a masterpiece because he had all these elements he had to weave together and the cinematography was just brilliant because they had to match all that stock footage ambiance and it looked perfect. And we had this experimental filmmaker named Jordan Belson who would make all these liquid crystal images and they’d put them in the cockpit … it was very exciting.

GP: KEMs or Moviolas?

SR: Some of the people worked in KEM rolls. Lisa worked on a KEM, I worked on a Moviola, Tom worked on a Moviola – I think Doug did too and can’t remember what Glenn worked on.

GP: Did you ever cross over from the Moviola to the KEM?

SR: Never … well, I would use the KEM to screen but not to edit. In a way the Moviola is a lot like the Avid because it was instantaneous – you grab it and it would be right there. You don’t have to spin down a 1000’ roll. The other thing is, I always objected to making select rolls. I felt like if you did that you limited your possibilities.

So when I got there it was all shot and really long and it was just so loose. It was plump beyond proportion; everything was taking twice as long.

GP Sounds like it was like an assembly.

SR: That’s exactly right … and the flight scenes were a disaster, so the first thing I did was breaking the sound barrier. They were shooting special effects all throughout post-production … models on wires, CO2 cartridges in the tails and thrown out of windows, all done very seat of the pants. The supervisor was Gary Gutierrez, very gifted and he should’ve won the Oscar. They had a backlog of about 50,000’ of special effects shots that weren’t used for some reason and I went through every frame of them and I used a lot of them, the plane uncoupling from the B-29 bomber for instance.

And the other thing that I did that no one had done in this fashion was, in the first cut when the airplane would go through the frame it was only eight frames long. You’d be inside the cockpit for a bit and then whoop you see the plane go by, and then you’re back in the cockpit and then whoop again for the plane. And so I got the idea of stringing a lot of those whoops together – whoop whoop whoop – and making one sound effect for the whole thing, and for some reason I knew immediately that’s what I had to do because you couldn’t have an eight frame whoop and then go inside, you just couldn’t do it. With the sound you could get away with anything and it worked great. It was like a revelation to everybody and to me it was obvious.

Those were the only sequences where I needed sound to convince myself it would work, and even in those days you never want to show anything silent to the director. In the very old days of film editing they used to show stuff silent, but soon it became much easier for directors to understand what you were doing if you had the right sound. So either I would lay it in or have one the assistants do a KEM mix.

And then during the final mix the sound editors had cut different perspectives for each little whoop and I said, “No, just use one like in the work track.” There were arguments but they did it and the sound guys all won Academy Awards.

There was an army of sound people and the mix went on for months. Mark Berger was brilliant and he had a really unique way of mixing where he would work on one track at a time. I mean I’d never seen that before – he’d go through the dialogue A track and smooth it and then B … Randy Thom did sound effects and he’s gone on to become a legend. And I think Todd Boekelheide did the music and he was the brother of the supervising sound editor. We mixed in single reels and I think there were 26 reels. It was a prodigious task and Mark did an incredible job herding everybody.

SR: And Phil had this theory that he needed to be fresh so the less he screened it, the better off he felt he would be. When we did screen it was for the producers, or Alan Ladd Jr. would come up from L.A. The producers were always enthusiastic … I mean, they had something to say but they were a good team, very astute. Their company was the house that Rocky built.

So when we finished the mix I don’t think we’d seen the film for months, at least two months, and when we finished the mix we took it to a big theater to screen it and lo and behold it was fabulous! No one had seen it in such a long time and it just worked. We all walked out of there on a cloud.

It didn’t preview … you can’t preview a 3.5 hour film no matter how good it is. But we did have a screening at the Kennedy Center and Walter Cronkite savaged the film. He was not happy because he felt it made fun of the astronauts, which it did to a certain extent. And the part of the film I disliked the most was with the chimpanzees, the training … but you know with Phil, if he wrote it, it’s in stone. The Australian bit was, to me, a little hokey too. But you couldn’t have gotten that scene out with dynamite – that was in the film forever. I remember working on a scene with him on another film and I said, “Maybe we should take out something there,” and then I saw his reaction, so then I said, “How about those two words?” And he said, “Oh, ok.” He’s such a brilliant writer, it’s just too bad that … I mean, he had a great career but it should’ve been a lot bigger.

GP: Talking about the running time was there ever a plan to have an intermission?

SR: No, I don’t think so.

I remember when it came to the music, originally it was going to be Vangelis. We sent him scenes but never got anything back so we had to find someone else. Then it became John Barry and that didn’t work out, and then the producers suggested Bill Conti and I thought he did a brilliant job. When we saw what he did at the end we were whooping it up, it was that amazing. Regarding the songs, we had a music editor and she came up with a lot of them like the song “I Got A Rocket In My Pocket” and that was brilliant. I’d never heard that song before and it just knocked my socks off. It captured Quaid’s personality.

There are only two movies that I suggested lines for and the director did them: Here it was when Alan Shepard is waiting to go up in the rocket and he has to pee, intercut with the gathering of the wives having coffee. I suggested the idea that became the wife’s line, “Alan must’ve had five cups of coffee before he went to work today.”

One of my best editing friends is Richie Marks [ACE], and we were both up for the Academy Award at the same time, our group for The Right Stuff and him for Terms of Endearment. We all thought Terms was going win, because The Right Stuff’s box office … it made no money and Terms of course made a lot. Technicolor used to throw a party for all the nominees and everyone was there and we were all pre-congratulating Richie: “You’re a shoe-in, congratulations.” And then when the night came we won, and he was extremely gracious about it. I think about him almost daily. He and I had the same outlook, which was: What’s so special about what we’re doing? I mean there are too many editors who’re exalting themselves. I mean ok, it is an accomplishment but, you know, we’re not the director or the writer and you know, we do our job well and that’s the scope of it. And we both worked really hard, really long hours.

He was very talented and he was always one step ahead of me with Dede [Allen, ACE]. That’s how we met. My first movie, my first feature film was Alice’s Restaurant and Dede had left me a note because I was working around the corner from her to come to see her but Richie was the one who could hire me or not. And his wife liked me and recommended me to Richie and that’s how I got the job. That was the most exciting day of my film career. Richie, Jerry Greenberg [ACE], Craig McKay [ACE] were all her protégés. Later I hired Craig McKay to work on the 1978 Holocaust miniseries and he and I won the Emmy for an episode. I was the supervising editor and each episode had an editor.

GP: What was your relationship like when she moved here (to L.A.) and became an executive?

SR: We were friendly; she didn’t recommend me for much. But I always loved her … two people are mostly responsible for my career, she and Arthur Penn. They were the ones who got me started and they were the ones who pushed me. Mostly as an assistant but I became co-editor on Night Moves which, if you’ve ever seen it, is incomprehensible. We looked at each other and said, “What’s the script about?” And Dede said, “Well he’ll make something out of it.” And there were a few movies he didn’t make something out of! Arthur Penn was just the sweetest guy, just the kindest gentleman, and the unbelievable thing was his movies had such violence.

Dede once said to me that cutting action is easy – you can do anything – dialogue is hard. And she was right. With action you can almost try anything. I remember when I was working with her on Night Moves and I expressed a fear of cutting action scenes and she said to me, “Oh, then you’ll do the last scene in the movie,” which was this big action thing. And yet if you have an actor who forgets his lines forget it – you’re stitching and frantically scrambling. There’s nothing that spoils a scene like a bad performance.

George Roy Hill hired me on Garp because Dede wasn’t available, and never asked me to do a movie again so I assumed he didn’t like me but then he became a friend.

But to get back to The Right Stuff, it was almost like a company, everybody was into the teamwork, even though there were clashes.

GP: Did editors recut other editors’ scenes?

SR: No you pretty much stayed with the same stuff. And once Tom Rolf came on – he was the last editor on – there was a better sense of teamwork … somehow he loosened things up. And I think one of the reasons we won the Academy Award is because Tom was very popular among the editors of Los Angeles. He won the ACE Award that same year for a different movie (WarGames) which didn’t get nominated for an Academy Award and so I thought that gave us a little bit of an advantage because not too many editors up to that time won from different cities – mostly it was Hollywood. Although Jerry Greenberg and Alan Heim [ACE] won for different pictures and then they moved to Los Angeles.

The Right Stuff, it didn’t make a lot of money and they didn’t really promote it very well because it wasn’t strictly a Warner Bros. picture. In those days Warner Bros. didn’t put the same umph into releasing other peoples movies like The Ladd Co. as they did their own. I forget what the Warner Bros. picture was at the same time, but I think a lot of the attention went to that instead of The Right Stuff. It never got a decent shot in terms of publicity and hype

GP: And there was also a weird conflating of the movie with then-senator John Glenn’s presidential ambitions, and that became news at the movie’s expense unfortunately because people assumed the movie had an agenda that it didn’t.

SR: That’s true, and I don’t really know what the astronauts’ opinions were but I don’t think they would have been that happy, because at the same time it praised their heroism it kind of made fun of them and instead of gods they became human.

GP: The movie only concentrates on two or three astronauts and yet there are seven.

SR: And some of them don’t even have any lines, and it was written that way. It mostly concentrates on Ed Harris, Fred Ward, and Dennis Quaid. It was something that you just accepted, they’re all there but we follow the story of just a few of them. And the last thing Phil wanted was movie stars … it introduced Dennis Quaid in his first juicy adult role, and Fred Ward and Lance Henriksen, among others.

Chuck Yeager used to hang out a lot – he and Sam Shepard couldn’t be more different, physically. And when Yeager was a test pilot he was just, like, a kid you know? “Send me up!” and then became, due to Tom Wolfe, a heroic figure.

I was invited to join ACE after Holocaust and I had to fill out the credits to submit to ACE and I couldn’t remember them all and was agonizing, “Would I have enough? Should I include this one?” and so finally I said, “Eh, forget it.” So I never joined and I’m sorry that I didn’t because I think that it does have a purpose.

The great thing about Phil was that he had an adventurous attitude about film where, a lot of times he’s doing it for himself; he’s not really doing it for the audience he’s doing it for himself, and it was hard for studios to convince him to do something he didn’t want. But it was such an amazing project because I was working with things I’d never seen before. And as I said, when I started on the film I was fiercely competitive, and I think I remained fiercely competitive throughout my career but I think I’ve mellowed.