Episode 6 (Jan 2025) – The Diplomat

Isabel Sadurni interviews Picture Editors Gary Levy, ACE and Agnes Grandits, ACE; Re-Recording Mixer Dan Brennan; Sound Supervisor/Re-Recording Mixer Sean Garnhart; Music Editor Robert Cotnoir; Assistant Editors Tracy Nayer and Matt Nickelson. The Diplomat airs on Netflix

In Season 1 of Netflix’s dramatic television series The Diplomat, showrunner Debora Cahn (The West Wing, Homeland, and Fosse/Verdon) launched a seemingly fantastical storyline in which a U.S. diplomat is rerouted against her will to become a candidate as America’s vice-president in check against a manipulative operator dedicated to advancing their own interests in a corrupt administration which has tolerated or even orchestrated terrorism against its own citizens for political gain. Now in post for Season 3, Netflix’s hit political drama has been nominated for a PGA, DGA and WGA award. Isabel Sadurni spoke with key members of the post editorial team about the evolution of their work and how the show continues to challenge and surprise them. Picture editors Gary Levy, ACE, and Agnes Grandits, ACE; re-recording mixer, Dan Brennan; sound supervisor/re-recording mixer Sean Garnhart; music editor Robert Cotnoir; and assistant editors Tracy Nayer and Matt Nickelson gathered via Zoom. Season 3 airs fall 2025.

______________

Isabel Sadurni: One crucial element in a show’s success is establishing a signature tone and rhythm. Can you talk a little bit about how the tone and rhythm of The Diplomat evolved over time?

Gary Levy, ACE: In the beginning of Season 1, we had this preconception that The Diplomat would play in a similar tone to Debora’s previous shows, like The West Wing. We really pulled the first three or four episodes apart to stop what felt too close to re-playing that. There was a lot of work in Season 1 figuring out what the tone of the show really was.

Sean Garnhart (sound supervisor/re-recording mixer): Once we all figured it out, the tone remained consistent.

Isabel Sadurni: For me the dialogue is honest, provocative and completely absorbing.

Agnes Grandits, ACE: The writing is what guides us. The writing and the humor and, I mean, the actors are amazing.

Robert Cotnoir (music editor): One of the first things I said to Deb when I met her was that I love that the characters talk like people actually talk in real life, as opposed to a sort of two-dimensional, “There’s the bad guy, let’s go get him” kind-of dialogue.

Gary Levy, ACE: We discovered early in the editing of Season 1 that the heart of the show is Kate and Hal’s relationship. So even with this world of complicated politics going on, you don’t mind if things go by that you may or may not completely understand, because you’re so deeply anchored in the intimate, personal and complex relationships between the characters.

Robert Cotnoir: The music can also zoom in and out, meaning, we might build out a big music cue at the start, then zoom in to a quiet cue to support a more intimate exchange. So the score can be big and small at the same time.

Dan Brennan (re-recording mixer): Because it’s a political drama, any given episode may deal with international conflict, wars, battleships getting blown up et cetera, but then, in the same scene, we might zoom into a room of three people having a very private conversation off to the side, and the rest of the world falls away. When we do that with music, like Bobby was saying, we’re telling both pieces of that story.

Sean Garnhart: A great example of that is in Season 2, Episode 3, where there’s a huge July 4th party, tons of people, music’s pumping. From a sound perspective, once we’re with the characters, we don’t hear much of the party because we need to hear the dialogue. Our M.O. for each episode is often to explain sonically where we are and what’s going on and then get the heck out of the way so that all the fast-moving, awesome dialogue can be heard without any distraction.

Isabel Sadurni: Throughout a season, you’re working with multiple directors who inevitably bring their own approach to the material. What’s your baseline? How do you ensure consistency of that tone and rhythm over a season?

Gary Levy, ACE: Debora asks us all to put our heart and soul into everything we do, which is what she does herself. Our baseline is in her guiding eye and ear on everything. She’s stylistically very [minimalistic]. Many of her notes are about doing less. Often, she chooses elements she wants to expand or play with a little bit, but everything usually ends up being tucked away.

Sean Garnhart: It was tough finding her sonic palette because of how [minimalistic] her approach is to this show. That’s only because she’s extremely tuned in, knows exactly what sound cues are playing and why they’re playing. For instance, there was a scene where a group of important dignitaries were gathering in a room that had squeaky wooden floors and chairs. Debora was very attentive to when and why to include those squeaky, creaky sounds as a way of speaking to the historical nature of the space and the august nature of the subject at hand. You want the audience to feel those uneven, creaky floors because they’re drawing parallels to aspects of the drama.

Agnes Grandits, ACE: In Season 2, Episode 1 there’s a scene where the main characters arrive at the embassy. We started with tons of ADR to explain where-is-everybody, are-they-okay, are-they-still-alive? Then by the mis, we pulled almost all of it out because we had found other, better ways to communicate that same information.

Matt Nickelson (assistant editor): The process is really just getting it in there, trying a lot of stuff, and then see what sticks. It’s an evolution of pulling things back to a more refined version.

Gary Levy, ACE: The sparseness gives it the grounded quality that we strive for. We want everything to feel very organic. Deb is resistant to anything that feels manipulative. She wants things simple and clean. In the process of getting there, we might throw a lot at a scene, but then we usually pull it back to a much simpler version.

Isabel Sadurni: Sometimes, it’s that sparseness that makes the tension simmer. Can you talk about how you build and maintain that tension in a political drama?

Sean Garnhart: It all starts with the writing. For me, the writing is providing the foundation of suspense. The mix process and sound-editorial build is very much an exercise in control and holding back and choosing just the right sonic assistance to the already compelling story.

Robert Cotnoir: Musically, there are very few filigrees. From very early on, we agreed to keep anything too decorative out of the system.

Dan Brennan: We don’t handhold transitions either. We don’t build those musical bridges you often hear in a lot of shows. Honestly, it’s because the narrative moves so well. I don’t even miss it. I’m just like, let’s get to the next part. I want to know what’s happening.

Isabel Sadurni: Can you talk specifically about the interplay of sound and picture in building that tension?

Sean Garnhart: We’ve had a few instances on the mix stage where Gary or Agnes or Debra have heard how sound or music is helping to propel a scene forward, and they’ll make a picture change to support it. We’re very aware of how we affect each other and there’s a willingness to change picture if we need to, depending on what music or sound is doing, as opposed to, “Well, picture’s done. Now, sound comes in to do their thing.”

Dan Brennan: We explore everything together in the mix. I’ll bring some stuff, Sean brings stuff. Bobby’s reworking cues all the time and we’re trying to see what’s going to really make it sing. You have a sense of it when you start, but you don’t know for sure how any of it will turn out until it comes together on the stage.

Isabel Sadurni: Being on a show with multiple seasons, I imagine there are familiar grooves you work into the story and characters’ arcs but also new challenges you confront each round. What was the challenge cutting Season 3?

Agnes Grandits, ACE: The challenge is that we shot out of order, so it was hard to track what was going on.

Gary Levy, ACE: We’ve been cutting scenes from all over the arc of the season which can be confusing. They just got done shooting in London and now they’re shooting in New York. The sound team is not yet on, but Bobby and Agnes and Matt and Tracy, we’re all doing Season 3, as we speak. We’re at the stage now where we’re getting footage that fills in the gaps from across the season and it’s starting to make sense. But, no question, it’s challenging to do eight episodes out of order.

Tracy Nayer (assistant editor): One thing that surprises me, being that the show is a political thriller, is how much temp VFX work there is. There are a lot of explosions, fireworks, and a lot of monitors. In sci-fi you assume there will be visual effects. But it turns out political thrillers have a bunch.

Robert Cotnoir: My challenge was that my tendency was to get too sad musically. There was always a melancholy behind my temp tracks. Maybe I’ve been listening to the news too much. I feel like none of what’s going on in real life should even be happening. It seems so absurd. Over Seasons 1 and 2, Debra would mention the absurdity of it all, but there’s an absurdity that’s also very gravely serious. You’re talking about nuclear submarines and everything in between. What I look forward to as we get into the lock, is when our composer, Marcelo Zarvos, adds the correct humanity to each spot. That’s when, whether it’s a serious queue or a fun queue or a sad queue or whatever, there’s always that thread in the score that delivers a dose of humanity.

Agnes Grandits, ACE: Also, I love the collaboration with Deb. She always finds solutions to make sure things are clear and the audience can follow.

Gary Levy, ACE: Deb may give a note saying, “This scene feels too slow,” and my instinct is to politely nibble away at it. Then she’ll come in and remove whole chunks of dialogue and the whole scene will click.

Robert Contour: Or, there’ll be an orchestrated cue and she’ll be able to come in and say, “Take Violin #2 out,” and it becomes a whole other thing.

Gary Levy, ACE: There are some shows that you work on where you’re editing around mistakes. It might turn out great, but getting there, it’s not as fun. That’s not the challenge here.You’re really selecting from an abundance of great performances and choosing the ones you want and shaping them and getting the tempo right. It’s such a joy to be dealing with this level of writing, acting and directing.

Dan Brennan: It’s fun to be on a project where you’re also a fan. I get so pumped when we get cuts. I’m like, ‘Oh yeah!” like, “Let’s go!” I can’t wait to see what’s going on.

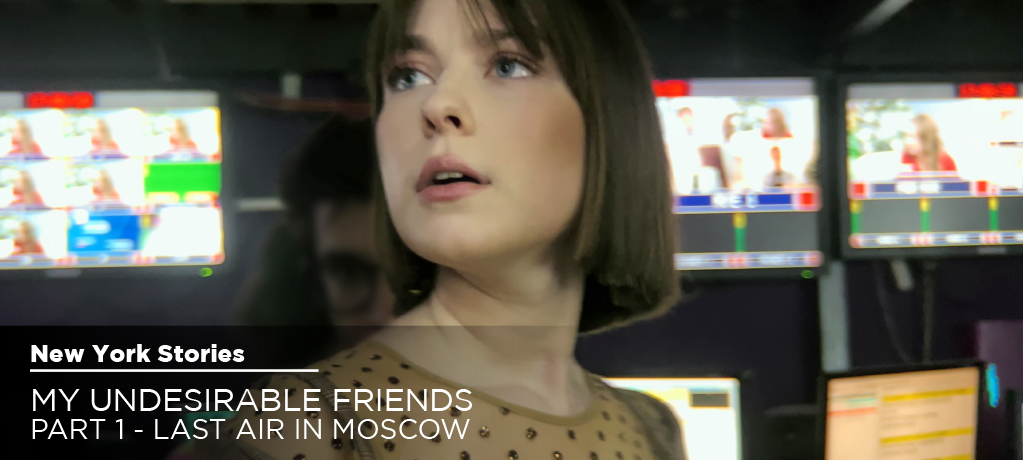

Episode 5 – My Undesirable Friends: Part 1 – Last Air in Moscow

Isabel Sadurni interviews Julia Loktev (Filmmaker/Editor) and Michael Taylor, ACE (Editor/Co-Producer).

My Undesirable Friends: Part 1 – Last Air in Moscow is part of the Main Slate Selection of the 62nd New York Film Festival.

My Undesirable Friends: Part I – Last Air in Moscow, is a 5 ½ hour documentary film by New York-based filmmaker Julia Loktev (The Loneliest Planet, Day Night Day Night) and her frequent collaborator and editor, Michael Taylor, ACE (The Farewell, The Loneliest Planet, Day Night Day Night). Critically recognized as one of the best non-fiction films of the year, it is at once an indictment of fascism and an absolution of the independent journalists in Moscow who risk their lives to continue working under the oppression of today’s Putin regime. Shot entirely on an iPhone, the film witnesses in arresting emotional candor and intimacy, the lives of several journalists and activists forced to mark themselves as “foreign agents” and ultimately flee a country they love. Each of the five chapters is paced and structured in a way that not merely holds its grip, but thrusts you forward toward the cliffhanger ( Part 2 is currently in post-production). Julia Loktev and Michael Taylor, ACE, joined me in conversation via Zoom.

______________

Isabel Sadurni for ACE: Can you talk a little bit about how and why you started this project?

Julia Loktev: I started shooting in October of 2021, four and a half months before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. I started out shooting a different movie than what it ultimately became. In late summer of 2021, I read a story in the New York Times about Russian independent journalists who had just started being declared “foreign agents” by the Putin regime who were fighting back with dark humor. It had a photo of these two cool-looking girls that looked like someone I might meet on my street in Brooklyn, except the Russian government had deemed them “foreign agents.”

I’m originally from the Soviet Union, and I was nine when I came to the US, so I followed news from Russia and I had friends there that I’d made as an adult, including Anna Nemzer, a journalist at TV Rain who is also co-director of the film. TV Rain was Russia’s only remaining independent television channel. It’s where people, for example, watched Navalny’s return to Russia live. If you’ve seen the documentary Navalny, a lot of the footage in that film was from TV Rain.

Anna and I thought the film was going to be about a society declaring journalists and activists “foreign agents,” in effect, forcing people – to mark themselves as “other.” I remember thinking what if you could have filmed in Germany in 1935, when the Nuremberg laws were first passed and people were first forced to mark themselves as “other.” I had no idea I would be capturing a society on the eve of starting a full-scale war and turning to full-blown fascism, and that I would be capturing the last days of the opposition fighting from inside Russia before all independent media was shut down in Russia and a million people fled into exile.

Russia had, of course, started a war in Ukraine in 2014, but it seemed to be a level of war that, absurdly and wrongly, the world had gotten used to enough to let Russia host the World Cup. No one expected the kind of full-scale war that Russia would start in February of 2022.

IS: Given that so much of the story changed from your original conception of it, how did you approach the material structurally?

JL: I thought I was filming a feature film, and then history started unfolding in front of me and I had to keep shooting. We got the chance to live through history in real time with our characters. And it turned into a documentary epic in multiple chapters. Part I – Last Air in Moscow all takes place in Moscow in the months leading up to the full-scale war and the first week of the war is 5 ½ hours. We are now working on Part II – Exile.

After I had whittled the footage down from about 300 hours to about 80 hours, I showed it to Michael. He was the first person to see the footage.

Michael Taylor, ACE: We had this amazing first week where Julia and I watched the footage for 5 days straight, for 8 or 9 or 10 hours each day. I had never done a documentary series or a 5-and-a-half-hour film. But the material called out for a more expansive approach. There was so much detail and depth in the lives of these characters as they struggled day by day. Julia was constantly present with her iPhone, right in people’s faces, so the footage is very intimate. Consequently, we were able to cut the film so that it felt like these characters are talking directly to the viewer. The frame was a window on this sort of oppositional journalism and activism as it existed in late 2021.

JL: Which is impossible to imagine in Russia today. I was shooting with an iPhone X then I upgraded to the 13 and 14, which responded to dark situations much better, and I had a little external 58 mm lens. That camera physically required me to be so close to the character, so it wasn’t fly-on-the-wall observational. It was more fly-in-your-lap. You’re really living life with the characters, hanging out in kitchens, taxis, at work.

Michael and I have worked together on two fiction features before this [Day Night Day Night, The Loneliest Planet], and as soon as he started editing, he said, “I’m just going to approach these scenes as if they’re actors, to think where do I feel them.”

MT: Julia had known journalist and TV host Anna Nemzer (Anya) before starting the film. But most of these characters she met for the first time on a Zoom meeting before she came to Russia. You look at the footage, and you get the feeling that Julia has known these people forever. There’s an incredible openness. I think that comes again from the camera and being patient, so they become completely comfortable with Julia and her iPhone inches from their faces.

JL: I’m very grateful to them for how open they were.

IS: I imagine there’s a kind of immediate solidarity as fellow media makers under the circumstances.

MT: Something that taps into that is Anya’s dinner party near the start of Chapter 1. It was the first footage I watched, because that’s literally the first thing that Julia filmed. She had landed that day.

It’s a typical Anya-type dinner party with 10 or 12 activists chatting about the fact that [Dimitry] Muratov got the Nobel prize that day, not Navalny, so you get an overview of where Russian politics and journalism are at that moment. This was about 6 months after Navalny returned to Russia and was immediately jailed. Originally, that’s how the film opened. Then we decided the viewer needed a primer on Anya and TV Rain upfront, so we shuffled the order.

The beauty of the footage was simply bearing witness. Julia does not guide her characters. It’s simply happening. It’s like watching a cat. The cat’s going to do what the cat is going to do. And these journalists, they’re going to do their laundry, they’re going to show you some T-shirts they’ve designed.

One of my favorite scenes is when Ksyusha goes to the post office by the prison where her fiancé is imprisoned. She hasn’t had any access to him for more than a year, and she’s creating care packages for him. You see box after box of Oreos, Cheetos, and instant coffee being lovingly packed. If we were making our own Dardenne Brothers-style movie, I don’t think we could have composed a better scene. But it was real life, and truly emotional.

We wouldn’t look at a scene and say, “Well, this is the one where we learn that the government has come down on this aspect of society.” Instead, we asked, “What struggle is this character engaging in at this point? What is important to them?”

In my own work, I do go back and forth between documentaries and fiction. And a few years ago working on Semi Chellas’ American Woman, I had this revelation which I wrote about in an article for Filmmaker Magazine, which I called “The Art of Listening.” I realized that actors will tell us what the scene is really about. Ignore the script. Watch what the actors do. See what you respond to. And that’s exactly what we did here.

JL: I shut up most of the time very deliberately during the shooting. I didn’t want to center myself. I heard a talk by Bob Woodward once, and it was one of the best lessons ever. He said, “You just have to shut up.”

MT: You have to remember, that this entire film is handheld by Julia, and the camerawork is steady and patient. Every editor wants the shot to go on as long as possible. An editor never wants a cut to be forced upon us. That’s one reason why I found the footage so remarkable. Julia let these people guide her. She didn’t guide them. She didn’t shut them up.

JL: I don’t shoot B-roll. For example, when we see Moscow, we really see it only in the window of the car behind our characters. I’m really focused on the characters, and I can be very patient. And then it’s a matter of distilling the essence of the scene in the edit.

MT: I knew working with Julia that we weren’t going to have cutaways to work with. We weren’t going to have traditional reaction shots. It’s just a matter of “you find a way,” and Julia is especially good at finding ways to connect things that might not normally connect in editing.

When we did The Loneliest Planet, we ended up with about 106 shots in the entire film, because after the beginning they’re all 3- or 4-minute long single takes, very beautifully staged one-ers, with no visual cuts whatsoever. A huge amount of sound editing went into all of those scenes – that’s how we were able to shape them. Everything I’ve ever done with sound in film I’ve learned from Julia.

There’s another thing. This film has a very different pace from The Loneliest Planet. It’s closer to Day Night Day Night, in the Times Square section. We’re very much going moment to moment to moment to moment in the film and there’s a lot of time compression in terms of keeping the pace going.

As far as our editing process for My Undesirable Friends: Part I, we passed everything back and forth. Julia would give me a bin, and she would call it “Master and Selects: 1st scene.” And she might give me 30 minutes, and say, “See if you can turn this 30 minutes into 15 minutes. Call it an assembly. Please don’t make it too polished. I just want to see how you see the material.” Am I describing that correctly?

JL: We really worked in scenes, and it’s a process of distilling each scene, finding the core of a scene. I shoot a lot because I don’t know what’s going to happen and I’m not trying to control what’s going to happen. So there’s a lot of nothing in between. Let’s say there was 4 hours of raw footage for a scene, and I would do a pass to throw out the garbage and cut that down to maybe 1 hour and have that subtitled. Then cut it down to maybe 40 minutes of selects. Then I’d pass it to Michael who would cut it down to, say, 20 minutes. It was really important to me to see what he responded to, what he found interesting. Then, he’d give it back to me and I’d cut it into a 5 minute scene, because I love editing and I love fine cutting. I’m very specific about what frame I cut on. I can micro tweak forever. I often cut on sounds, on a sharp sound. I like when you feel the cut. I want the cut to be a little disturbing, a little surprising. Where I think Michael is so incredible is thinking about the big picture. So once we had cuts of all the scenes, then we’d sit down and watch an assembly of the entire chapter together, and start to think of the big picture of the chapter and adjust the scenes from there. And Michael is an incredible judge of performance. For my fiction films, I operated and Michael sat behind me in the proverbial “director’s chair” and would say, “That’s good. That’s not good. She’s really great in this scene.” He was basically doing my job. And I was doing the reverse. It’s so important having that collaborator who knows the footage inside out, who can write it with you. It’s not so much hands you need, but a brain.

IS: And a heart. Someone who’s really feeling the film.

JL: Exactly, and Michael is very instinctual. He will tell you when this moment doesn’t feel true, whereas I might be focused on the precise rhythm of something. In that way, we’re a very good team.

And he never stops thinking. The next day, he might say, “It was bothering me last night when I thought about this moment that doesn’t quite ring true. What if we connect this to this?” And usually I say, “No, no, no, no, it has to be this way.” And then, a day later, I’ll say ,“You were so right. I should have listened. You’re right.”

MT: On our previous films, I had learned with Julia that if I made an argument for something and Julia said, “No, no, no,” to just let that go for a little bit, and maybe it would come back. Maybe it wouldn’t.

With this film, I started to realize that certain characters fulfilled different roles within the scenes.

JL: We very much thought in terms of editing it like you would a fictional workplace series where in each episode one character comes to the foreground.

MT: Right. So for instance, I felt Sonya is one of our most accessible characters. The way she shared her own experience through showing us her house, saying things like, “We thought maybe I’ll decorate this living room, but we don’t know how long we’re going to be here,” and then, a month later, “Now, we have a sofa!”

JL: Something that so much of the film is about is how everyday details convey a bigger picture. For example, there’s a scene where one of the characters shows us a couch she just bought. She had been declared a foreign agent by the Russian government a few months after she moved into an apartment with her boyfriend. So when we first meet her, she has this almost completely empty living room because she doesn’t know how long she is going to be able to stay in the country and keep working as a journalist. And when we come back in Chapter 2, she announces, “We bought a couch!” It means she is planning to stay; she thinks she still has a future in Russia. Of course, this scene was shot in December, and two months later she has to flee because Russia shuts down all independent media and starts jailing people for just calling the war a “war.”

MT: All of these characters are now living in exile. We’re currently editing the next section of the film, Part II – Exile, where we continue following these characters as they move from country to country continuing their work outside Russia. There are hints of the storm that’s coming as we move from chapter to chapter. For instance, you meet this young guy, Daniil, briefly in the first chapter, who has been declared a “foreign agent” and is talking about moving to Poland. Then, one chapter later, we see Sonya say, “Here’s the plant that he left me.” So we know he is not there anymore. He’s in Poland. But she has the plant. She’s showing us a plant, but it means more than that.

IS: I wanted to ask about something that I really appreciated about the film which was this ability to weave humor and levity throughout a very dark narrative. How intentional were you about that? There were obviously moments I’m assuming that came organically, and you welcomed and incorporated those. Were you also rhythmically aware that the audience needs a break and “Let’s watch the cat” for a moment? Can you talk about finding the emotional balance of the film?

JL: I think there’s humor in The Loneliest Planet and Day Night Day Night. There’s dark humor in my first film Moment of Impact which is about my dad being hit by a car. It’s how my mom and I dealt with that event, a trauma which most people think would not invite humor. But of course, there are inappropriately funny moments in the most tragic events in life. It’s always been how I’ve dealt with the most difficult situations in my life. It’s just in my DNA.

I’m instinctively attracted to those moments. This is aside from the fact that our characters are naturally very funny. For example, Ira and Alesya, two of our journalists – their office has been searched, they know it’s bugged, there’s a drummed-up criminal case against their editor and he’s had to flee the country, they continue to work in their office, and they live constantly in fear of being followed, of someone showing up at their door. And they tell this story about how Ira’s doorbell rings one night and she thinks she’s about to be searched. So she puts on “search appropriate underwear.” They then discuss what is “search appropriate underwear” that it has to be not too embarrassing, but it also has to be comfortable enough, because you might be in jail for several days. To me, that’s what brings it home because that’s what I would be thinking of if I thought the police were at my door, and I might be hauled to jail, and I was in my nightie. I would also be thinking, “What kind of underwear am I going to put on for the next few days of sitting in jail?” That’s a very normal human reaction and it is funny, but it’s also very real. To me, it’s how we process the most difficult events.

MT: One thing that was also important to us is that we wanted to show the work process of these journalists. Some of them make work you can show in videos, like TV Rain, or Important Stories, which is Ira and Alesya. This work is on websites or YouTube. Some work in print for publications like Novaya Gazeta – that’s Lena. We knew we needed to show them actually doing the work of a journalist and what does the work look like? In the case of Anya, because she’s one of the prominent journalists at TV Rain, we could use TV Rain footage to show us “this is what’s happening.” Lena is a phenomenal writer. She has a book out called I Love Russia, which I recommend everyone to read. For Lena’s work scenes, we came up with this device of seeing her typing and then seeing her words appear on the screen.

JL: We knew that we needed to see their actual work, what they’re writing about to explain why the Putin regime would not be happy with these journalists.

IS: Being in the company of people marked as “foreign agents,” did you ever feel that you were in danger? Or concerned that your iPhone would be confiscated?

JL: In terms of danger, I was constantly aware of it when I was around my characters, and I stayed in Moscow during the first week of the full-scale war when the US Embassy was telling Americans to leave while there were still flights. Flights were being canceled almost everywhere and I stayed. At that point, Brittney Griner had been arrested, but this was about a year before Evan Gershkovich was arrested. So I thought, I’m not a famous basketball player. Nobody’s really interested in me. I told myself that “I’m going to stay as long as they’re here,” and I stayed until all my characters fled the country that week and I had nobody left to film there … As they continued to report the truth of the war, they were getting constant threats. I did recognize someone could come into the TV Rain studio any moment, and god knows what, arrest us all, shoot us all up? I was aware of the dangers they live with constantly in their work, dangers they continue to live with in exile. There was actually an Opinion piece in the New York Times just this last week [September, 2024] called “Putin Is Doing Something Almost Nobody Is Noticing” about the Russian Secret Service pursuing activists and journalists abroad that mentioned physical threats to two of our characters. Whatever risks I took feel negligible compared to the risks they take continuing to report the truth. And certainly in comparison to the risks of just a regular person living in Ukraine now.

MT: As we were ready to start sharing the film, we started having these screening club sessions where we invited about 15-20 people to Julia’s apartment and projected each chapter. We’d have one chapter and then a month later we’d have another. We realized we could only invite the same people each month. We couldn’t shift it around because you needed to have seen Chapter 1 to understand Chapter 2. So we developed this core group of people who stuck with us pretty much through the whole edit.

JL: And they were the ones who really encouraged us to get Part I out now as we work on editing Part II – Exile.

MT: I really do think that the individual parts are wonderful, but when you take the cumulative effect of watching all of them together, it adds up to something even greater.

Find additional coverage of the film here:

The Best Doc of the Year Is Like a 5.5 Hour-Long Panic Attack, Vulture.com, October 5, 2024,

Episode 4 – From AE to Editor

Isabel Sadurni interviews Jasmin Way (Picture Editor) and Gordon Holmes (Picture Editor)

Assistant editors, akin to junior magicians in the editing department, are often assigned the task of performing feats of technical daring-do that complement the lead editors’ creative story sculpting. This by no means belies a lesser contribution to the craft of filmmaking. Here, New York based editors Jasmin Way (Rebel in the Rye, The Pentaverate) and Gordon Holmes (On Swift Horses, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom), share their experiences about how skills they developed as assistant editors continue to advantage them in securing projects as editors.

______________

Isabel Sadurni for ACE: The path from AE to Editor is so different for everyone. Can you talk about a pivotal project or person that helped set you on your course to becoming an Editor?

Jasmin Way: I started off in feature length documentaries and reality television and had already made the move from assisting to editing. But I’d always wanted to work in narrative. When the opportunity came along to work on a narrative feature, I sidestepped and became an assistant again. The first feature I assisted on was with editor Jeff Wolf, ACE, and it was called The Outskirts. My second feature was with Joseph Krings, ACE, and titled Rebel in the Rye. Both of them could see I could cut and really encouraged me. On Rebel in the Rye, Joe gave me some scenes and said, “Why don’t you cut 3 versions of this?” He gave me feedback and, eventually, worked some of my ideas into the film, so I ended up getting an Additional Editor credit. That was pivotal. Years later, Joe needed a second editor and he recommended me for a show called The Pentaverate for Netflix which ended up being my first big narrative editing gig. I wouldn’t be where I am right now without the wonderful people who have been mentors and given me those opportunities.

IS: What do you think you cultivated in yourself as an AE, that made those relationships so successful?

JW: As an editor, you want someone to bounce ideas off of before the director comes in or before feedback screenings, and that’s really your assistant. So if that relationship and that dialogue is going well, I think then editors feel like, “Oh, here’s someone who’s a collaborator, and not just someone who’s waiting to be told what to do.” I work really hard and I try to stay positive. I try to give my ideas when asked, but never force my opinions. People appreciate my figuring stuff out on my own and getting it done in a timely manner.

Sabine [Hoffman, ACE], another mentor of mine, always encouraged me as her assistant. She asked my opinion and wanted to have me in the room with her to watch stuff down. She was doing a recut of the film, A Thousand and One, and brought me in and said, “You’ll assist me, but we gotta do this fast and I’d love your collaboration.” When Sabine had to move to her next project, I ended up working for a few weeks alone with A.V. Rockwell, the director, and was credited as an Additional Editor. Rockwell then recommended me to the director, Aristotle Torres, for a feature that I edited entitled Story Ave. All those kinds of relationships and experiences build upon each other.

IS: Gordon. Same question. What was the pivotal phase that helped you move from AE to Editor?

Gordon Holmes: For me, it’s been a long and winding road: I’ve been editing narrative projects since ninth grade. But, there was a pivotal moment when I received an offer to cut a zero budget feature at the same time that I was offered a union position on the Aronofsky film, Noah. Obviously, the Aronofsky film was a great way to get introduced to supremely talented and intelligent people, and to become familiar with a high-level workflow. But also, I needed health insurance. So instead of the creative job, I went with the Aronofsky project to develop more technical skills.

Sometimes I wonder what my career would look like if I had taken the zero budget editing gig instead of trying to work my way up from the bottom as an AE. I’ve definitely found it advantageous to have credits from major motion pictures that most people have seen or at least heard of. Often, to sell myself for a feature film editing job, at the point when I hadn’t yet edited a feature myself, I would say that I had cut my teeth on jobs put together in big-budget Hollywood cutting rooms. I’ll never really know if I landed the job because of merit and chemistry, or if it was because they wanted to hear anecdotes about Aronofsky or Colin Trevorrow. Either way, the technical expertise I learned on bigger projects was invaluable when I was cutting smaller budget shows where I couldn’t hire a whole editing room and had to do everything myself. There’s a benefit to being a polymath who knows the technical side of workflow efficiency and who can sensitively craft a story.

When I learned that you can’t get an agent with micro budget indie credits alone, I strategically checkerboarded between editing jobs and union assistant and VFX editor positions, or what I call “AE/VFX editor jail.” It’s easy to justify taking those jobs but it becomes difficult to break free from being perceived as more technical than creative. Fortunately, I began to work with editors who saw me for what I always have been: a picture editor. People like Kate Sanford, ACE, and Katie McQuerrey were not only willing but excited to share their wisdom and help mentor the next generation. At first, I was doing assistant work for them. But I was sure to make pockets of time where I’d cut scenes to show them for their feedback. Before I knew it, I was cutting with the director(s) and earning credit bumps.

IS: Which is the perfect segue to my next question: Can you describe some of the essential AE skills that continue to give you an advantage over others that didn’t come up through the AE track?

JW: On a feature I cut last year called A New York Story, I had an assistant to do dailies, and another, at the end, for turnovers, but in between, it was just me: I did all my own sound editing, my own sound effects, temp visual effects, my own music editing, things usually given to an assistant. Obviously, having more hands would have been ideal, but because of my background as an AE, I was able to achieve a polished look on my own, without an assistant.

In fact, a feature I cut that just premiered at the Venice Biennale called The Fisherman also had AEs at the beginning and end, but again, in the middle, I was a one woman machine. This was an English language film shot in Ghana. The dialogue had a thick accent, so I subtitled the entire movie. There‘s also a talking fish so I placed all of that VO and I put in all of the visual effects. Again, bringing a high-level skill set to a project when, say, a VFX editor isn’t available, can make a big difference.

IS: Gordon, were there opportunities that came to you because of your broad skill set?

GH: I always remember my growth as an AE/VFX editor on Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. I gained extensive experience doing temp VFX which expanded my ability to mine, manipulate, and optimize performances in ways that aren’t inherently obvious, including being able to do complex split screens.

On that project, one of the biggest challenges was to find ways of making an adaptation of an August Wilson play feel more cinematic. One way we did that was by supplementing shots to enhance their sense of dynamic playfulness. For instance, there was a moving shot with two characters, and editor Andy Mondshein, ACE, asked me to comp another character from a different setup into that shot. But the shot with the third character was static, so I was just like, “What do you mean? The camera’s literally swinging around in one shot and there’s this guy just standing there in the other.” After days of rotoing and using all the tricks in the VFX editor playbook, it worked! I surprised [director] George [C. Wolfe] and I surprised myself. It helped us recognize the architecture of the scene and we were able to move forward. I always tell younger assistants that being able to identify the need for hybrid performances and being able to quickly perform a clean split screen in front of a director are important skills to have in an editor’s tool belt.

IS: Assuming you’re hired for your creativity and your understanding of the material, what technical knowledge gained as an AE, have you found puts people at ease most often when speaking with them as an Editor?

JW: Working with first-time directors, I often get questions about finishing like: “How are we gonna do x-y-z once we get into color and sound?” Being able to provide detailed answers based on previous projects gives them the reassurance they need. As an AE, you also learn about the politics in the cutting room. You learn not to alienate anyone or step on toes. That’s not a technical skill, but it’s equally as important.

Last year, I worked as an assistant for Kate Sanford, ACE, on the Hulu series We Were the Lucky Ones. Even though the show was completely remote, she very kindly included me in many of her zoom sessions with the director and then showrunner. I was able to observe how she deftly handled notes and different personalities with ease. When it came time to present my work to them, Kate would always include me and I ended up with an additional editor credit on that project.

IS: Looking ahead, can you share something of a current or future project that challenged you in new ways, that you’re also really excited about?

JW: I mentioned The Fisherman that just premiered at the Venice Biennale. It was really nice to have that in person experience with a large audience, and with the director, Zoey Martinson. Especially because this was a comedy, hearing an international audience respond and laugh really brought the film to life. We won the Fellini Gold medal, which is a UNESCO award given to a film that best embodies values of peace, tolerance, and inclusion. I’m still kind of riding high off of that.

IS: Congratulations! I feel like that’s another reason why we all need to watch films in the theater. We need a big group of people around us to really feel the film.

GH: I recently cut Willie Nelson’s 90th Birthday Celebration, a star studded concert film/ documentary featuring stars like Snoop Dogg, Sheryl Crow, Helen Mirren and Ethan Hawke. After a theatrical run, it’s now streaming on Paramount+. And I just finished working as an additional editor under Kate Sanford, ACE, on the film, On Swift Horses, which premiered at TIFF. The spirit in that cutting room was ideal. Instead of having rigid tiered levels of power, it felt like Kate, [director] Dan (Minahan), and I were all equals working to find the best shape of the story. The tone of any cutting room is set by the senior editor so I credit Kate for enabling such a creatively fertile and collaborative environment. Anyway, the project kept getting extended to the point where we ran into a scheduling conflict. Because Kate had so generously enabled my creative exposure to Dan, the director, he knew that I was capable of taking the film to the finish line. I’m proud of that work and so grateful to mentors in our community like Kate who actively help their AEs move up.

Episode 3 – The Bear

Isabel Sadurni interviews Joanna Naugle, ACE (Picture Editor), Adam Epstein, ACE (Picture Editor) and Steve “Major” Giammaria (Supervising Sound Editor, Re-recording Mixer)

The FX television series, The Bear, continues to deliver clever, compelling drama as proven by a steady current of awards recognition over the course of three seasons (on September 15 The Bear won eleven Emmys, breaking its own record for most comedy wins in a single year).

I spoke (via Zoom) with Joanna Naugle, ACE, picture editor and partner at Brooklyn-based Senior Post, Adam Epstein, ACE, picture editor and Steve “Major” Giammaria, sound editor and re-recording mixer at Sound Lounge, to talk about how their collaboration continues to bring imagination and energy to the show.

Isabel Sadurni: The visual and aural grammar and language of the show you’ve created is so unique. Can you talk a little bit about how it continues to evolve?

Joanna Naugle, ACE: One of the things that audiences love, and I think that we love about the show is when we take a moment to spotlight characters. As editors, our task is to figure out how the pace of an episode should change based on whose story we’re telling. All of Season 1 is Carmy’s perspective. That’s where we figured out the tone and pace of the world of Carmen Berzatto. In Season 2, we spend time with Marcus, we spend time with Sydney, we spend time with Richie.

I remember Adam and I co-edited the episode, “Honeydew,” (S02E04) which focuses on Marcus in Copenhagen, and we were cutting it so fast with all this loud music, and it felt a lot like Season 1. Christopher Storer (creator/executive producer/writer/director) and Josh Senior (executive producer) said to us, “I think Marcus’ episode should be more meditative, show Marcus’ world as an island of calm within the kitchen.” We translated that to letting things play a little bit longer, focusing on his process of using the precise measurements in baking. Without making it feel like a completely different show, I think we’re able to, subconsciously, take you into a different character’s world.

In Season 3, there’s an episode called “Napkins” which focuses on Tina. We establish how she’s so efficient, how it’s important that she arrives at the exact right time, and she keeps checking the clock. When her world spirals out of control, we break our established rhythms. There’s a sense of disarray, and to translate this, we were cutting so that things maybe are not falling quite on the beat. That’s happening in the picture editing. Once we get to mix, we talk with Major about what we’re going for. And he has a million ideas about using different sound effects to reflect her state of mind and enhance what we’re trying to show.

This is a way that I think the language has been evolving.

Adam Epstein, ACE: I think the progression of the structure and tone from Season 1 to Season 2 to Season 3 mirrors the progression of the restaurant itself. In Season 1, you have chaos. In Season 2, it’s about breaking something down and then building it back up and trying to install a different rhythm. This then became our guiding ethos, picture and sound wise. With the third season the restaurant is established. But now the question becomes, “How do we maintain this?” Ideally, we’re using form and structure to mirror the characters and their emotional states. The location and the thematic aspects of what’s happening with the restaurant itself is a blueprint for a lot of what we’re trying to get across with the editing.

Isabel Sadurni: Can you talk about your day-to-day relationship as collaborators that helps generate this energy and emotional momentum in the show?

Joanna Naugle, ACE: We usually don’t wait for picture lock to add in a sound design and mix pass from Sound Lounge and that’s pretty unusual. Maybe around the third edit, we’ll still be cutting and getting notes, and we’ll send it to Sound Lounge for the first mix. Immediately, upon hearing what they’re doing, we’ll start getting ideas, playing with it and saying things like, “Oh, yeah. I didn’t even think about how we could get more stylized with the sound effects here.” Being able to start the conversation and establish a common vocabulary with the sound team earlier makes things so much more creative for us.

Adam Epstein, ACE: From a collaboration standpoint, I think we both try to set up Sound Lounge with reference material that’s as detailed as possible, to hopefully remove the guesswork. Often, I’ll send it off thinking, “Well, that sounds pretty good,” but then we get it back from them and we’re like, “Oh, my God! That’s the ne plus ultra version of where we had started.” Major and his team are always able to take our offline sound design to a level we could never get it to.

Major Giammaria: Both Adam and Joanna are so amazing and give us such great scaffolding, or a structure to play on with plenty of room to add texture and depth. That’s the best place for us to start. A common challenge for sound editors is finding room, both horizontally [time] and vertically [texture, complexity] to fit in a compelling sound design that supports the story and characters.

Ironically, a lot of times, The Bear is very densely layered, but there are moments that you guys make sure to carve out temp sound that’s strategically placed so we can do what we need to do. We can say, “Okay, I see what they’re doing rhythmically and structurally. I see what they’re doing tonally.” I’d say about half of Joanna and Adam’s temp stuff ends up in the final. Thank you both for all of that.

Isabel Sadurni: Can you share an example or an anecdote, or experience where, through the collaboration, something unexpected opened up?

Joanna Naugle, ACE: In Season 3, there’s an episode where the Fak brothers show Carmy the wall they’ve made of all the critics’ headshots … it was such a funny scene, and we really wanted to get into Carm’s head in terms of him being stressed about getting the Michelin star(s). Adam created this really great panic attack montage of all the possible stressful things Carmy’s thinking about at that moment. And I remember we were debating, “Is this working? Is this not working?” Once again, we got the sound mix … and the team at Sound Lounge just took it to the next level: We were hearing Chef David in the background, we were hearing a little bit of the review they read in Season 1, we were hearing the haunting ticket machine from Episode 107.

Major has a great depth of references having worked on the entire show. We have our ideas picture wise of the things that would be flashing through Carm’s head, but he was able to bring the little things aurally that could cause anxiety, or things that could be echoing in Carmy’s head, where we hadn’t fully nailed it. When the sound came in, we responded with a few ideas and then it was, like, “Oh, yeah, this is really working.”

Adam Epstein, ACE: Every once in a while, I’ll hear something that they added to the mix and I’m like, “That’s so great – we have to use that again somewhere!” In Season 1, there’s a great zoom in on a clock where they layered a bunch of unpredictable sounds like dark laughter, and then panned that audio in really unique ways. Interesting sonic choices from the sound team really elevate and enhance the scope of a moment in ways that offline sound can’t.

Oddly enough though, in a show that’s known for being as loud and manic as The Bear, it’s in the much slower, quieter moments where thinking about final sound has changed my approach to a scene. For instance, if there’s a scene centered on two people talking, the offline audio tends to have things like the creaking of the floor, or subtle changes in the ambiences when cutting between different takes. Major and his team are able to add what I call “the professional quiet,” a background that’s non-intrusive, but still rich with the life of that environment – and that allows us to linger much longer in a scene. Knowing that they’ll be able to add that rich ambience to a quiet dialogue scene, trusting that it will play well, and be able to just live in itself, really helps my process as a picture editor.

Major Giammaria: Again, it all starts with the scaffolding that the picture editors’ team brings forward. Because you guys leave room not horizontally, but texturally, we can play in the peripherals of what you’re hearing, and go for that subtlety which is fun for us. I remember there was a shot of Marcus outside looking at a flower, and we brought in, whatever, a Harley-Davidson motorcycle driving by two blocks away. But it’s that kind of stuff that adds a texture and depth to a moment that I think helps an audience sit in those shots. It helps us paint a whole picture which is the point, right?

The two questions we typically ask ourselves are “What is really happening in this moment in the characters’ world?” and “What emotionally is happening for the characters as it relates to sound?” So, if there’s a scene where, say, Richie is having a quiet moment in the office, and it’s 2 o’clock, we’d ask, “What prep work would we actually be hearing outside? Does that support what we want to feel emotionally in the scene?” It can get pretty granular because you’re thinking in terms of textures to support the emotion. In fact, I got a note from Josh once, that was like, “Hey, there are too many forks off screen here. We need more plates and dishes.” It was because, sonically, the forks were too percussive and too intrusive to what was going on. We needed more of an easy, steady, dishwashing rhythm.

Isabel Sadurni: Along with bringing us into the internal state of the characters, can you talk about how you’re also raising the stakes, visually and aurally, building in what drives us to the next beat, or the next scene?

Joanna Naugle, ACE: During “Ice Chips,” the episode where Sugar is waiting to give birth, we talked a lot about how we wanted it to feel really realistic and natural at the beginning. Major and SFX editor Jonathan Fuhrer made it feel like you were actually in the hospital, layering in sounds of people talking outside, machines beeping and people wheeling things down the hallway. As we get into the more intimate part of the conversation, where we use more close-ups, the outside sounds melt away, so you’re not distracted by them. Choosing the moments where we want to draw the audience in is a combined effort of focusing picture and sound perspectives for sure. I also want to shout out Megan Mancini who’s not in this conversation but did such a phenomenal job editing that episode!

Adam Epstein, ACE: I find it interesting the way we use music as far as “Is this score or is this diegetic?” Usually where we end up, it’s neither, or it’s this kind of middle ground, where it fluctuates between being an obvious score that’s driving the scene, or an underlying base that isn’t in the room, but supports the emotional standpoint of wherever the character is at. Finding that balance is something that the sound editors have really nailed and that’s given the show a unique musical feel.

Major Giammaria: It’s a tricky balance. You guide us through it and usually have a very specific map in mind of energy and pace that’s to be supported by the music. If the music is playing as an underscore I’m thinking of it as another texture, poking through at very specific between-syllable moments, almost like a background. We try to make sure everything’s heard clearly and we don’t shy away from asking questions when we need to.

Adam Epstein, ACE: A hundred percent. Those questions from you guys are so helpful. Things like, “Who would we be hearing in the other room at this point?” make us think deeper about a scene. “Well, if we’re seeing them in the next scene, we might hear them in the background here too, and so on.” These first reaction notes from Steve and the sound editorial team can open up our picture editing as well.

Joanna Naugle, ACE: You’re also the first people to see a semi-locked cut outside of the producers. I remember when Evan Benjamin, our dialogue editor, saw the first episode of Season 3 and said how much it impacted him emotionally. That was a really reassuring moment for me since that episode was a big swing stylistically and I wasn’t sure if people would connect with it or not. It’s just so helpful to see the things you guys are responding to or getting excited about, or pushing further. It really feels like such an organic process. It requires some reconforming and maybe a little more back and forth, but I think it makes for a better and more collaborative end product.

NEW YORK STORIES – EPISODE 2

Gaucho, Gaucho

a documentary film by Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw

ISABEL SADURNI INTERVIEWS Gabriel Rhodes, Picture Editor / Stephen Urata, Sound Designer, Re-Recording Mixer / Fatima de los Santos, Associate Editor

New York-based documentary picture editor Gabriel Rhodes is known for his work on the Oscar

nominated film, Time, Emmy-award winning The First Wave and Peabody award-winning

Newtown. For this year’s Sundance Jury Award-winning 2024 documentary, Gaucho Gaucho,

he worked in collaboration with verité documentary cinematographers and directors Michael

Dweck and Gregory Kershaw (The Truffle Hunters), Sound Designer and Re-Recording Mixer

Stephen Urata (The Truffle Hunters) and Sevilla-based Associate Editor Fatima de los Santos to

tell the story of the rural subculture of the Gaucho community, their passion, spirituality and their

profound symbiosis with nature as they work to honor and preserve their cultural legacy in the

mountainous Salta region of northwest Argentina. New York-based editor, producer, and writer

Isabel Sadurni, interviewed the team via Zoom.

IS : This is the third feature from duo Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw, who met each other

in New York. Gabe, how did the directors invite you to get involved?

Gabriel Rhodes: They’d seen my previous films and reached out to me by email and said, “We’d

like to have a conversation with you about this.” I hadn’t yet seen their previous film, The Truffle

Hunters, and when I watched it, my jaw hit the floor. They’d created such a unique cinematic

language, so I got very excited. They sent me the deck for Gaucho Gaucho. At that point, they

had some footage and when I looked at the deck, I was just like, “Oh, my God.” You could

instantly see from the images what this film was going to be and how it was going to be

applicable to the style that they had created with The Truffle Hunters.

IS : Were they shooting simultaneously to your edit?

GR: Yeah, the whole way through. They traveled to Argentina to shoot at least three times

during the edit. Fatima, our Associate Editor had built a trailer for the film prior to my coming on

board. The look and feel of the world had manifested by that point, so there was already

something for me to sink my teeth into.

Fatima de los Santos: I started working with them after they had traveled to Argentina about four times. In total they would make seven trips. While they were filming in the field, I would review, mark the best moments, and together we would select the best shots for each character, imagining their possible arcs and anticipating how we might construct the teaser.

IS: Can you talk a little bit about your editing process, what your timeline was like, and how you

evolved the characters.

GR: When I came on, they had already selected the main characters. There were several of

them, so the question became “Are we keeping all of them?” The unique thing about the way

they film is that they meet with each character, engage in their world and get to know their story,

which of course, allows these people to open up to them. From there, they explore the pathways

for how the story for each individual character can unfold. They might say, “We’d like to shoot in

this location with you talking to this person about something roughly like this” believing that’s

going to drive the narrative of this person. Those dialogue scenes were generally an hour,

sometimes longer. Typically, they like scenes to play without an edit, or very few cuts. So the challenge is always to

find the stretch of dialogue or conversation that fits the narrative, however simple it may be. Like

one was, “The condors are attacking my flock, and so I need to protect them.” But with docs,

you can’t anticipate exactly how the characters’ stories are going to develop during the shoot,

so, you’re still sort-of figuring out what that narrative is going to be as you go. They would

schedule more shoots to reinforce the narrative that we discovered within the edit. My timeline

started in May of 2023, and we had a picture lock by early December 2023. So it was pretty

quick.

IS: How were you receiving dailies in New York from the remote mountain regions in Argentina?

GR: The dailies were uploaded from Argentina to Fatima in Spain, where Fatima and her

assistant, prepped, synced and translated subtitles. Then Fatima sent that to me in New York.

FdlS: My assistant, Julio Castaño, created proxies and synchronized incoming footage, while I

would view and classify all the material. The translation and subtitling were hard because,

though I’m a native Spanish speaker, gauchos speak with a very thick accent. And one word

can change the meaning of a whole sentence. So we brought a team of local translators led by

Christina Hodgson, to make sure the translation was accurate for every single segment. It was a

process because we were working through 100 hours of footage.

IS: There were so many strikingly beautiful compositions and emotionally intimate moments in

the film. I’m imagining within those 100 hours there was a lot to choose from. What was guiding

your narrative choices?

GR: Each of the characters that Michael and Gregory chose, embodied this sense of freedom

that they were working with thematically. I’m thinking of Lelo, who’s the older gentleman with the

white beard, and his desire to just ride away, and live in the freedom that he remembers from

his youth. A lot of Lelo’s material, whether it was sharing stories of his past when he was a child,

to talking to his wife about the desire to get away, to talking to his daughter and reminiscing

about his adventures, led us to begin to piece those together and figure out how to understand

this person through his stories. Then there’s the two little kids, Pancho and Lucas …

they’re just on a ride, you know? At one point, we asked ourselves, “Do we need to explain where they’re going?”

There was material of them saying, “We’ll meet so and so up on the hill. Eventually, we just took it out

because we decided you didn’t want the explanation. You wanted the feeling of watching them be

free to ride out into this desert landscape. But, Fatima, you should talk about your first exploration of the

footage.

FldS: When I was editing the teaser, all the footage was beautiful, and you love a lot of

moments, but as Gabriel said, the priority was to tell the story with the image and not

necessarily with the dialogue. Being Gaucho Gaucho is something beautiful. The documentary

has to transmit this idea and the audience has to feel it, too. So the film had to strike just the

right balance between locations, feelings, and music because music is also very important to

the gauchos.

IS: The credits list field sound recordists, but no dedicated sound person as a part of their team.

Is that right?

Stephen Urata: They did pick up a recordist for each shoot on location, but sometimes they

recorded sound by themselves. To that end, they did an amazing job gathering sound for the

film. It really helped me establish “place” for the film because for various reasons, I was forced

to build many environments from scratch. There’s one really beautiful recording they gave me. I

mean, you hear it and you’d assume it’s sound design or a sound effect, but it’s an actual field

recording. It’s the sound of frogs.

IS: Stephen, as the Sound Designer and Re-Recording Mixer how did your relationship begin

with the project?

SU: I had gotten to know Greg and Michael through a program that Sundance and Skywalker

Sound put together. Sadly, it’s not around anymore due to budgetary constraints, but they used

to put on this annual sound design lab through Sundance where various people from Skywalker

Sound would volunteer to be a guest sound designer for different teams. As a participant, I got

paired up with Greg and Michael working on a vignette they’d put together. It was around five

minutes of footage from what would eventually become The Truffle Hunters. We loved working

together so much, they asked me to stay on to work through the full-length feature. Even then,

they were already talking about the Gaucho Gaucho story. I was, of course, excited because I

knew what they could do and what it was going to look like. We stayed in touch the whole time

during the Gaucho Gaucho shoot, but I didn’t dig in until around September. Then we worked

through early January in order to make Sundance.

IS: Was there one moment or scene in the film that was exceptionally challenging?

SU: I love the way they shoot, as if setting up a still camera, because those long sound takes

give me a little bit of time to sit in the environment and experiment with different aspects of the

space and build-out the environment with sound, even though we’re also focused on the

conversation. The greatest challenge sound-wise for me in this film was probably creating a

believable sound of a condor. There were very few location recordings of condors. I had to take

the sound they recorded, and stretch it out, slow it down, add a lot of reverb, make it sound

bigger for different moments.

They spend a lot of time miking up with lavs and booms and trying to get really good recordings

of the environments. So I had pretty decent audio to work with.

IS: What were you starting with audio-wise as a base layer? It sounds like you had a lot of great

material.

SU: Gabriel’s sound design in his edit for Gaucho Gaucho is amazing. I really appreciated what

he handed off to me. I try to respect the essence of the Guide Track as much as possible while

approaching the aesthetic of a film. That preliminary soundtrack is tremendously helpful for

more complex projects, and especially helpful for projects with shorter timelines. There’s a

purpose for every sound in the picture editorial timeline, whether it’s to serve the story or make

us feel something. The tracks help inform me of conversations that took place between the

directors and editors, almost like a blueprint or letter to the post-sound team of their intentions. If

I can offer one piece of advice to picture editors, if you have a sound team that you trust, stick to

the essentials and don’t feel pressure to fill up the timeline with a lush soundtrack. It will allow

some room for our imagination.

GR: Thanks, Stephen, though, I would say that sound is not my greatest strength. I definitely did

what I could with what I had to work with and filled in the blanks. Honestly, when I watched the

film for the first time after Stephen did his pass, it felt like a whole new film, like a whole new

dimension, had been added to the film that wasn’t there that I couldn’t bring to it through picture

editing alone. I was blown away by how much was pulled into the film. I was there at Sundance,

and I can tell you, the whole room froze from the very first frames when you hear the sounds

that Stephen starts the film with over black.

IS: That opening moment was incredibly powerful for in the way that the sound and the image,

both so elemental, are working together. And the intimacy that they were able to create, as if a

horse and a man are sharing the same breath. You really did have us from Frame 1. Often the

schedule can be too tight for a sound editor to create that depth of layers or detail that you

created for this film. Were you given a little bit more time on this film than you perhaps have had

on other projects? Or have you developed a shorthand with the directors? What was the

process like for you?

SU: Michael and Greg and I certainly have a shorthand. After working on Truffle Hunters, I

understand their aesthetic. And, yes, their focus and love for sound is probably five times

greater than your standard documentary film timeline. They do care about it enough to secure

funding for Sound specifically.

I’d like to also give a shout-out to the Foley team which was Heikki Kossi, who now heads up

Foley at Skywalker Sound. There’s a scene with Lelo trotting along on his horse and every

sound related to the horse is built from scratch. Anything from the leather creaking, the metal

bridal and reins, to every horse hoof hitting the various ground surfaces.

GR: They’re incredible. Before they came on, though, those riding scenes were especially

challenging because in the raw footage, the main audio I was hearing was the “Rrrrrrr” of the

camera truck. Anytime you see the camera moving horizontally or pushing in on a follow-shot,

they’re on a camera truck with a really loud engine. It took them days, by the way, to get a

camera truck up into those mountains. But in those shots, it was a little bit like blind editing,

because you have to basically remove the production audio to feel the pace and the tempo of

the image. Then it’s like hoping and praying that when the film has edited audio, it’ll play the way

that you’re imagining. So you’re trying to evoke a feeling through the image and the audio that

you don’t have control over. Thankfully, I was in good hands.

The film will next screen at the Locarno Film Festival on Wednesday, August 14, 2024. Find

information for additional festival screenings and news of a future release date for Gaucho

Gaucho on director Michael Dweck’s website.

https://www.michaeldweck.com/films/gaucho-gaucho

NEW YORK STORIES – EPISODE 1

ISABEL SADURNI INTERVIEWS JOSEPH KRINGS, ACE

I spoke with editor, Joseph Krings, ACE (CAPTAIN FANTASTIC, AFTER THE WEDDING) from his editing suite in New York where he’s working on his next project DEATH BY LIGHTNING to talk about his work crafting THE GREAT LILLIAN HALL, directed by Michael Christopher, starring Jessica Lange and streaming on HBO. Interviewed by Isabel Sadurni, ACE, New York, NY, June 10, 2024.

ACE: How did this project come to you?

Joseph Krings: The Great Lillian Hall came to me through my agent, but really it was because one of the producers of Lillian Hall is Bruce Cohen. Bruce and I had worked together on Rebel in the Rye, and got on really well, and he thought this was a good fit for me. I set up a meeting with Michael Cristofer, the director. I assume Michael liked my interpretation of the material because it was just a couple of days later when we started figuring out the details.

ACE: How or when did HBO get involved?

JK: HBO acquired the project as a completed independent film. They’ve really believed in the project and released it on the last day of consideration to push Jessica Lange for an Emmy.

ACE: The director, Michael Christopher is a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, an actor, and a director, whose play Man in the Ring also deals with a protagonist confronting dementia. Can you talk a little bit about working with a director, actor and writer who’s been soaking in these themes for a few years?

JK: This material was clearly in his wheelhouse in terms of subject matter and Michael’s been in the theater since the 70’s and knows that world. He’s directed plays, he knows what it’s like to be an actor, what it’s like backstage and in front of the house. As someone who loves the theater, and loves actors, I think he saw a chance to create a space where you care about all the theater people in the film.

Photo by Dia Dipasupil/Getty Images

ACE: Talk a little bit about how you built that compassion for the characters in the edit.

JK: Our working process was a really good back and forth. They shot in Atlanta. I got the material in New York. At first, we talked about the basics: protecting the performance, looking for authenticity, pace, and determining what’s essential to know and what’s not essential to know to deliver the most emotional outcome. I did the assembly to, essentially, the script on screen. In that process, we discovered that it felt very “seeing, seeing, seeing, seeing”. The opening had the lead saying all these lines from the play walking around her house, and going outside, but you didn’t know they were lines from the play. Then we see the whole scene in rehearsal, and then we know the lines are coming from the play. But that was a lot for the audience to hold onto, to understand it. Michael suggested “Let’s just see her say a line when she’s at home there, then we’ll cut to her saying that line at the theater, and then we’ll go back and forth.” That sort-of unlocked movie for us. We started doing it everywhere. And that became the language of the film.

ACE: What were some of the biggest obstacles or challenges during the edit?

JK: One challenge was that they shot for New York City in Georgia. So we had to be really careful not to break the illusion. There were some real gifts like Jackson and Washington Park in Atlanta, designed by Frederick Olmsted, looks exactly like Central Park. I mean, it has the same benches, the same lampposts. We put in some digital skyline, we put in driving plates of a car going through Times Square, we scoured for aerials in Central Park that landed on a particular balcony that looked like the balcony they shot, but it was tough. Also, I’d never intercut to the extent that I did for this project. The challenge was to make the intercutting not feel like a montage, but to make it feel dramatic. Once we started doing that, it got addictive. In fact, we had to take them back sometimes because I was like, “We can’t have this whole movie be one long intercut.” It was fascinating to learn how much more momentum we could gain if we started condensing scenes and running them together. We also had to make sure the inhabitants of the world felt like a real theater company, that the theater felt like a real place. A lot of that was done with the directing, but my job was to keep an eye on that and make sure that it never suddenly felt false.

ACE: Were you in conversation with any other films dealing with dementia or the world of the theater during the edit?

Opening Night (Dir: John Cassavetes, 1977) was a touchstone for both of us. It has a really full backstage life: you see the people, the agents, the director. You see the fans. You get this whole sense of the company. We talked about Vanya on 42nd Street, but it’s a very different movie. What’s interesting is that we talked a lot about sports movies, because in a way, Lillian Hall is built like a countdown to the big game. And will-she-won’t-she, you know? You start to root for somebody.

ACE: Did the project force you to learn a new technology or approach?

I made a conscious decision coming into this job to approach my workflow entirely differently. In the past, I was doing too much work on the front end, creating these giant selects reels that had everything. I was making tons of versions of cuts, but I wasn’t just sitting down and watching the dailies. So that’s what I did. I changed my whole routine. I sat on the couch and watched the dailies and took notes, and then went and cut. I cut fast and carefree and it opened up a whole new way of working. I found that I was more open to how things could potentially be put together and it saved time. It also kept my brain free to look at the big picture, not just be focused on “I gotta keep up to picture and keep set informed about how I’m feeling about things”. I was happy to learn that I could change my process and grow and get better at what I’m doing. The movie after that one worked the same way.

ACE: Are there guideposts that you set for yourself in the way that you choose to make versions of scenes?

JK: It’s the architecture of the shots. Like how does it work if you start the scene in a close-up and then go wide. Or start wide and then go in, that sort of thing? And then organically, the performance evolves. I learned from Tim Squyres, ACE, to do the cuts in the same sequence and turn on Dupe Detection, to help you not use the same footage anywhere as you make versions. The process helps you see what you like and what you don’t like. Let’s say you make three versions, then you make your hybrid out of what you like most about each. And then the scene starts telling you what it is.